Working the Archives

In February 2020, the Grierson Research Group held a Studio session called “Working the Archives”. The session was led by David Greene, Sophie Toupin and Rafico Ruiz, and served as a guide for those incorporating archival research into their scholarly work.

Each presenter thoughtfully considered how to approach archives, and provided insights into the physical/digital structures that house archives, as well as reflections on what it means to do archival work.

Here are some of the takeaways from each presentation:

David Greene

David Greene is McGill University’s Liaison Librarian for the Department of Art History & Communication Studies, the School of Architecture, and the School of Urban Planning. In his presentation, David outlined practical ways to approach some of the more daunting aspects of archival work: namely, how to understand and approach the organization of an archive, and how to manage your own archival work. He emphasized the importance of setting your expectations while working remotely: archives and special collections are still largely physical - the rate of digitization does not keep pace with the expansion of the physical material in the archives. Many materials are not officially catalogued and described, and even fewer have been digitized fully. This is why it is crucial to make connections with people in archives - they are your best resource for navigating the breadth and depth of a collection. If the archive at your home university/public institution doesn’t have what you are looking for - chances are your librarian/archivist knows someone who might be able to help you at another location.

Key Tips

1. Approaching archival work

• Set expectations - remember the limitations of working remotely and the pace of archival work

• Identifying archives - work your way back through a secondary source, consider location, and remember to ask for help if you get stuck

• Jargon - read up on Archives Terminology, and make use of any finding aids.

• Tips for research

Browsing is at least as important as searching. We are used to using search engines and searching for key words - this is not always the approach in the archives - immerse yourself in the collection

Make room for serendipitous discovery. By browsing you allow for things to emerge from within a collection

How things are described might not reflect their contents

Ask for help from a Librarian or Archivist

2. Digital archives and subscription-based primary source collections

• There are limitations when doing online research – but there is a lot available online, and the scope of this availability is increasing

• Don’t rely on Google -think locally, identify relevant institutions and browse those archives

• Large-scale digital archives - Projects like the Internet Archive are great search tools that can identify digital archives and point to digitized materials

• The library - the library at your home institution likely subscribes to databases of digitized archival material – ask your librarian!

• McGill-subscribed digitized content

3. Managing what you find

• Zotero - Zotero is a reference manager that works well with online material, its tagging and relating functions adapt well to archival research

Sophie Toupin

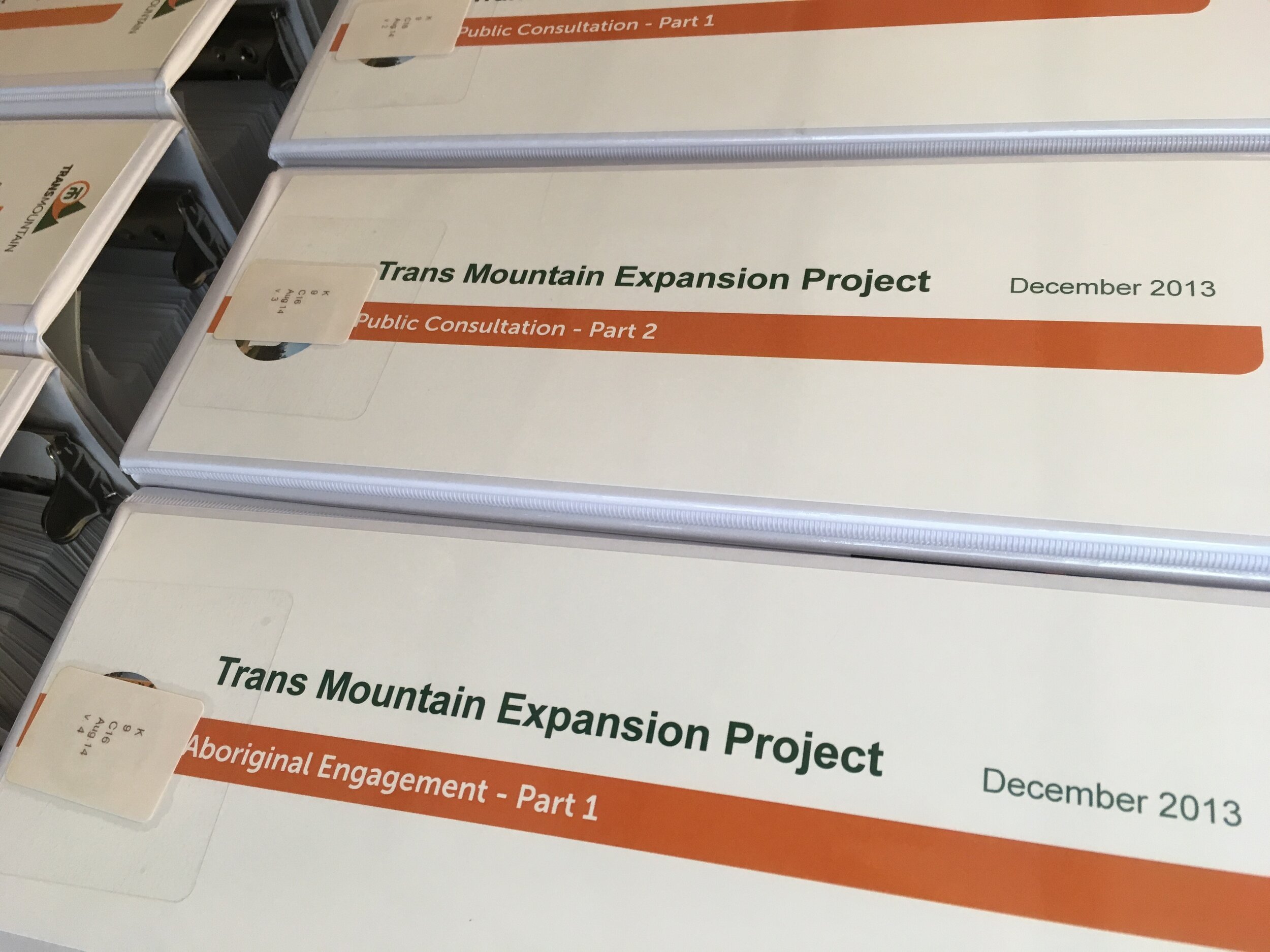

Dr. Sophie Toupin completed a PhD in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University. Her doctoral research examined the relationship between communication technologies and revolutionary movements in the context of the South African liberation struggle. Over the course of her research, she visited and consulted archives in South Africa, England, and Canada. Sophie’s reflections began with an important acknowledgement: archives are not neutral spaces.

An archive is, in fact, a highly political space and the materials contained have meanings that shift over time. The meaning of an archive is not fixed, it can be reinterpreted and re-read according to new ways of thinking. Take as an example the British government’s Kenyan Archive. In 2012, the British government was forced to reveal the existence of an archive that had remained secret for more than 50 years. This archive revealed the ways in which the British colonial administration had a policy of “targeted elimination” towards anti-colonial movements, and hid this history by concealing, reclassifying, and very slowly releasing compromising files.

Given the political nature of the archive, it is crucial to remember that access to certain material is not guaranteed. Depending on the nature of your work you may be prevented from accessing certain material. The politics of an archive is also clear in its contents and location, there are many artifacts that do not legitimately belong in the archive you are in – take notice of this in your work, use your political judgment, and consider whether the thing you are looking at actually belongs in the archive, and how that might influence your treatment of the material.

Key Tips

1. Prepare in Depth Before Arrival

• Talk to a former Ph.D student - especially a history student - they have specific training in archival work

• Make a list of archives - Consider archives that are state-run, in universities, part of social movements, corporate archives, and personal collections. Reach out to them well in advance

• Look at online catalogues - Identify materials of interest by speaking with Ph.D students who have done work in your area of interest/place of interest for tips

• Contact the archivist responsible for the collection you want to access - establish what you have permission to access and what requires specific clearances

• Consider collecting interviews and oral histories - The people you interview may have access to personal collections with materials and artifacts that are not available anywhere else in the world

2. Manage your Materials

• Managing the volume of images you take in an archive can be difficult - you can use open source apps (like Tropy, Taguette, or RQDA) that allow you to organize and tag your images, or you can use apps with paid access (like Nvivo, RQDA, VOSviewer)

• Take detailed notes after you leave the physical archive - you will almost always have a limited timeframe to work within while visiting an archive. Take photos of the material you access and make sure to regularly organize and take notes. This ensures you maximize the time you have without overwhelming yourself with material to sift through once your time at the archive ends.

3. Funding your research

• Government Funding - Michael Smith Foreign Travel Supplements

• McGill University Funding - AHCS + PGSS Funding

• Research Residency - MITACS Funding

• Archival Funding - Some archives offer funding for scholars to visit the collections

• Conferences - Conferences that are of interest in the country/city where you want to do archival work (the conference might pay for some of your trip).

Rafico Ruiz

Dr. Rafico Ruiz is the Associate Director of Research at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, and completed a Ph.D in Communication Studies and Architecture at McGill. His perspective on archival work stems from his work on The Grenfell Mission – a Protestant medical mission set in northern Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1890s. His research addressed how the Grenfell mission shaped and consolidated infrastructural mediation on the settler colonial resource frontier. In doing this work, Rafico had to dive into the mission’s archive, travelling to Newfoundland and Labrador’s “The Rooms” and visiting the contemporary resource frontier in the north of the province. His reflections on the archive began with an observation about the experience: it can be a messy process. Each scholar has to figure their way around their own particular archive. Take these tips into consideration but, ultimately, there is no perfect way to capture a specific history.

Key Tips

What’s My Object?

• Attend historically to the footprint your object left - also consider other dimensions of the story that are not immediately obvious

• Once your object is established, carve out what element you want to focus on and why. This will help you decide the amount of time you spend at each archive

• Remember that the archive you visit is situated in contemporary conditions - this will inform the interpretive framework that surrounds your object

What are my tools?

• Is your phone enough? Many archives allow for digital capture of materials

• Consider whether or not you plan on reproducing these photos - your phone is enough to make a record, but you might need higher quality images for reproduction and publication

• Record the location and moment of capture

Go there (and stay) and don’t count on going back

• Sometimes a return visit is possible and useful, sometimes it is not.

• Be realistic about how much time you need, and how much time you have

• Reading vs. collecting - Reading onsite allows you to be immersed in the world of your object, deciphering the records and images you collect will continue in the months that follow

• Think of archival work as a sort of field work - thinking about locations and physical infrastructures as places and people you want to get to know

• Plan to go, to stay, and (maybe) not go back- be comprehensive during your visit. While you are in a specific place, spend time in the larger context of the archive - look around!

I’m an Archive Creator

• Remember that you yourself are an archive creator, organize the material you create.

• It is important to consider how you will access the material you collect for future use

• Collect tangential material to your initial research question - this can form the basis for new research and new questions/projects

Next Questions

• Keep your next questions in mind - privilege the rare moment when you have the opportunity to look around and take stock of a place you are not familiar with

• Be conscious of the expanded field around your historical project, see what else is at stake around your object of research

Further Resources on The Archives

Achille Mbembe, Decolonizing Knowledge and the Question of the Archive (2015)https://worldpece.org/content/mbembe-achille-2015-%E2%80%9Cdecolonizing-knowledge-and-question-archive%E2%80%9D-africa-country

Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings (2003)

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995)

Kate Stewart, “The Secrets of Archival Research (and Why They Shouldn’t Be a Secret at All)” Medium.com (2019) https://medium.com/swlh/the-secrets-of-archival-research-and-why-they-shouldnt-be-a-secret-at-all-88dc611e0c41

Laura Schmidt “Using Archives: A Guide to Effective Research” (Society of American Archivists, 2011) http://files.archivists.org/pubs/UsingArchives/Using-Archives-Guide.pdf

Samuel J. Redman, Historical Research in Archives: A Practical Guide (American Historical Assoc. 2013) https://cbpotter.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/aha-archives_final-08-07-13.pdf

Archival Research Tutorial, York University Libraries (2006) https://www.library.yorku.ca/binaries/ArchivesSpecialCollections/Guides_York/Printable%20version.pdf

Text by Sian Lathrop

Images by Sophie Toupin, Rafico Ruiz and Darin Barney