The Automation Tapes

Andy Stuhl

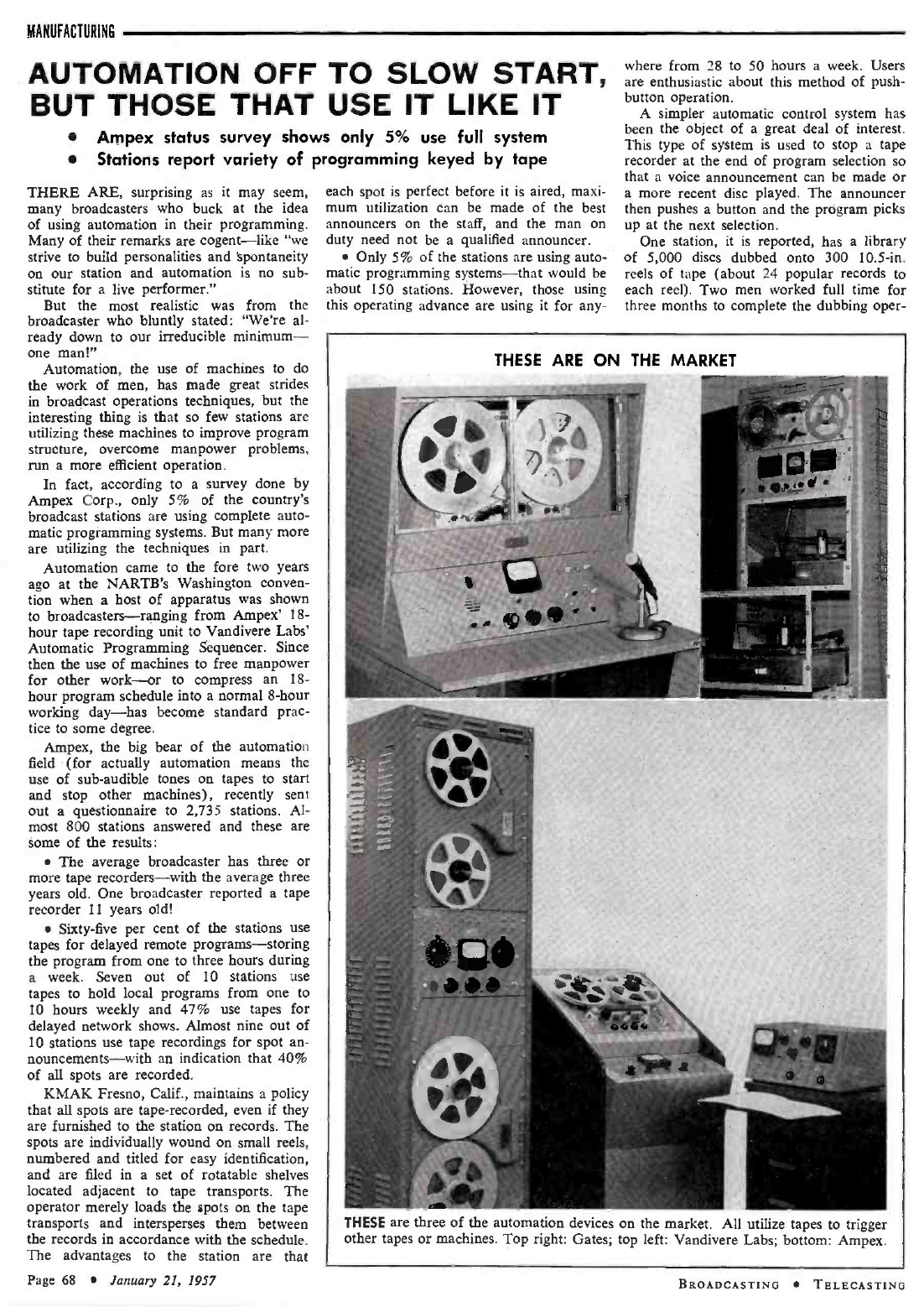

In my research into early forms of radio automation—a set of technologies that help select and sequence recorded sound ahead of its broadcast—I have been spending a lot of time looking through trade magazines from the 1950s and 1960s. One lesson these articles have for us is that the practice and meaning of "automation," which today might evoke the sense of a global, pan-industrial conspiracy among invisible algorithms and sleek robotic arms, has varied across the material and cultural contexts in which it has emerged. A 1957 article in Broadcasting/Telecasting first called automation "the use of machines to do the work of men;" just a few paragraphs later, though, the writer descended from that lofty and misleadingly gendered definition to explain that "Ampex [is] the big bear of the automation field (for actually automation means the use of sub-audible tones on tapes to start and stop other machines)." Illustrating the article are photos of several different tape reel players that could detect and respond to those automating tones, including a model from Ampex, the proto-Silicon-Valley company that had imported magnetic tape technology from German radio studios at the end of WWII. These unglamorous machines looked less like robotic DJ stand-ins than like filing cabinets with tape reels and a few control dials affixed to their fronts. The tape reels in these images echoed the author's parenthetical admission: in radio, automation was a property of tape.

A while after coming across the Broadcasting/Telecasting article (thanks to the digitization and preservation work of the World Radio History maintainers), I was browsing another online archive—this time the University of Pittsburgh Library System's digital collection for UE News, the periodical of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America—when I was struck by the cover of a 1961 issue on automation: here was another tape reel mounted on another vertical rack, front and center in the context of factory automation rather than radio automation. The main difference from the radio equipment photos was that this tape had holes punched in it. Perforated paper tape, like punch cards, was a means of computer program storage for much of the 20th century. Tape held a key advantage over cards in an automation context, in that a program meant to be repeated over and over again could be set up as a physical loop by having its tape ends glued together (Essinger, 2007). Manufacturers opted to use tape as a portable "program medium" instead of putting programmable controls on machines themselves in a conscious choice to distance the task of programming from the machine operator and thus reduce the control that shop floor workers wielded (Noble, 1984). The designers of this UE News cover clearly understood that tape, through specific automation designs, had become a weapon against organized labor. "Automation" stretches across the top of the image in large letters, followed by a series of block text: "Developed with the people's money | Seized by the corporations | Its benefits must go to all people."

To the left of the text, a dramatically lit man with a close-cropped haircut and shadowed eyes pulls the perforated tape out from its spool, performing an ominous yet ambiguous excavation. Is this man's hand the "visible hand" of large-firm managerial capitalism (Chandler, 1977) seizing technology for its own profit-seeking purposes and insulating automation from its potential socialist use to return time to laborers? Is his expressionless face meant to suggest that he is a figure of automation, manifesting a fear that users of automated systems would themselves become robots? (Radio engineer turned independent broadcasting advocate Jeremy Lansman expressed this anxiety: "Threading tapes into the blinking automation machine... made me feel I was little more than an automaton myself" [Walker, 2001].) Does his inscrutability suggest that he could instead be a Luddite or Promethean figure, disrupting the corporation-captured tape loop in order to return it to the people? Program tapes have been a target for anti-corporate and anti-government sabotage, as Gidget Digit recounts: "In 1970 an anti-war group calling itself BEAVER 55 'invaded' a Hewlett Packard installation in Minnesota and did extensive damage to hardware, tapes and data. More recently (April, 1980), a group in France (CLODO--The Committee to Liquidate or Divert Computers) raided a computer software firm in Toulouse, dest[ro]ying programs, tapes and punch cards." Pulling a length of tape from its reel, after all, could threaten the perfectly controlled timing with which automated systems aimed to regulate laboring bodies, by returning variance to the "total fungibility, efficiency, and assurance of unimpeded flow" whose disturbance would represent "sabotage" under its 20th-century redefinition (Williams, 2016).

What to make of the fact that people ranging from shop floor overseers to radio industry reporters to technological saboteurs have all understood tape as the physical body for the concept of automation? The radio context reminds us that tape was a medium where representation (content) and instruction coincided. A century and a half earlier, perforated paper tapes used in Jacquard looms had marked the start of a slide between pattern and program. The inaudible "cue tones" overlaid on top of song recordings, instructing another tape player to insert an advertisement, seized on that fluid combination in a system that physically separated choices involved in broadcast programming from their execution by DJs. By the 1950s, tape had become a widespread medium for storing and distributing sound recordings. Automation arrived in radio when this material that carried representations from place to place turned out to also be capable of carrying instructions. That arrival would be hugely consequential amid increasing centralization of the American radio industry and constantly shifting conceptions around work, artistry, and autonomy in sonic broadcasting. Unglamorous even in the eyes of the reporters who covered it in 1957, the simple technique of embedding these cue tones into reels of recorded music announced that sound had become software—and that radio workers would now negotiate with machinic counterparts designed to regulate their craft.

References:

“Automation off to Slow Start, but Those That Use It like It.” Broadcasting/Telecasting, January 21, 1957.

“Automation, the People’s Property, Misused by Corporations.” UE News, September 11, 1961.

Chandler, Alfred D. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1977.

Digit, Gidget. “Sabotage: The Ultimate Video Game!” Processed World, 1982. http://www.processedworld.com/Issues/issue05/05sabotage.htm.

Douglas, Susan J. Listening in: Radio and the American Imagination. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Essinger, James. Jacquard’s Web: How a Hand-Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Noble, David F. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Walker, Jesse. Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2001.

Williams, Evan Calder. “Manual Override.” The New Inquiry (blog), March 21, 2016. https://thenewinquiry.com/manual-override/.