Bait

Darin Barney

“No Gadus morua has yet turned itself into fish.”

Okay, nobody actually said that. Still, I swear I heard it (the wind?) standing there on the wharf at the Fogo Island Co-operative Society facility at Seldom, Newfoundland and Labrador. My friends and I had just bought a box of frozen Atlantic cod in the store and had wandered down to the wharf as a group of fishers were hoisting slabs of frozen squid onto their boat in preparation for the next day’s work.

Though Andreas Malm did say this about fossil fuels: “No piece of coal or drop of oil has yet turned itself into fuel” (Fossil Capital, Verso 2016).

This is true in general, and it is particularly salient in the context of capitalist resource economies. Between a thing and its use-value, and between its use-value and its exchange-value – between a piece of coal or a drop of oil and fossil fuel, or between Gadus morua and a quintal of saltfish or a box of frozen cod fillets – stand multiple mediating forms, labours, technologies, architectures, infrastructures (both physical and epistemic), practices and discourses. These are socially produced and reproduced, historically specific, and variable. Together, they are means by which elemental and environmental things are made into resources and commodities which, in turn, make and remake social, political and environmental arrangements and relations.

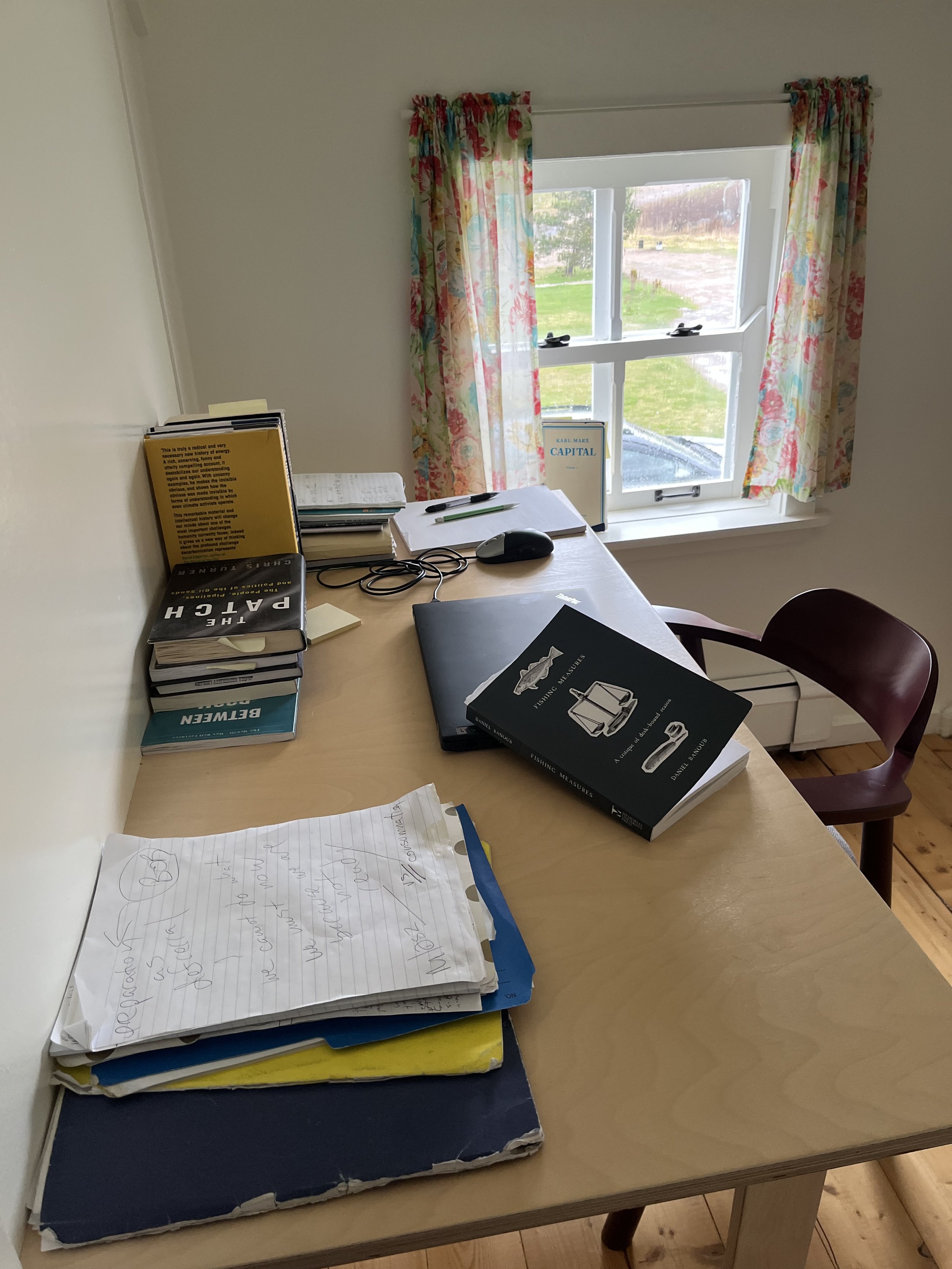

In his exquisite history of the Newfoundland cod fishery, Fishing Measures: A Critique of Desk-bound Reason (Memorial University Press 2021), Daniel Banoub calls this “making fish.” Here, in Newfoundland and Labrador, fish are made, not found, especially fish prepared at scale for export as a resource commodity. As Banoub explains, fetishization of “the cod” commodity tends to reify and obscure the conditions of its making. This is mirrored in scholarly, literary and popular cultural imaginaries that fix on what Banoub calls, “the extractive moment…the most charismatic moment in ‘fishing’” (32).

As he explains, imaginaries of “fishing” in the extractive moment include: “the romantic vision of the ‘hardy fisherman’ rowing his wooden dory a few miles offshore to hand-line fish, straining to pull the fish aboard. Or one might conjure up the image of a massive steel trawler, many days away from land, manned by alienated industrial labourers, mechanically hauling in thousands of pounds of fish with massive nets” (32). These distinctive harvesting practices and their respective technologies are crucial material variables in making fish and in the societies, economies and environments made and remade thereby. Banoub’s aim is not to minimize the impact of extraction but, instead, to draw critical attention to the less charismatic “moments” – or mediating forms, technologies and practices – that precede and follow the moment of extraction in making fish.

In a magnificent account of frontier- and resource-making in Labrador, Slow Disturbance: Infrastructural Mediation on the Settler Colonial Resource Frontier (Duke 2021), Rafico Ruiz makes a categorical claim: “The fish came first,” or “First fish, then mediation.” This could be misleading. Ruiz means to say that cod (as a species) were present in the waters off Newfoundland and Labrador long before

colonial dispossession and settlement, and that various mediating infrastructures were required to support extraction following its “discovery.” This is indisputable. The question is whether the cod were “fish” (an export commodity) before they were made so by means of the very forms of mediation Ruiz so expertly describes

Banoub documents multiple forms, technologies, infrastructures and practices of mediation that have preceded and followed the extractive moment in various phases of the fishery’s organization – not least of which is the commodity form itself. Many of these respond to the inherently unstable conditions of making a resource commodity from a “wild” biological organism in a complex, seasonal, and dangerous marine environment, for export at scale to far flung markets and fickle consumers – what Banoub describes as the “problem of fluctuation” (26). Among the forms of mediation that follow extraction, those that involved formatting the resource for storage and transportation (i.e., the preservation techniques and infrastructures involved in making saltfish, such as premises for salting split fish and drying them on flakes at the shore) have assumed an aesthetic and charismatic status of their own, while others (such as pricing) remain of interest primarily to political economists and other unimaginative people.

What about conditions that precede the moment of extraction? Here, too, distinctive forms of mediation arise in response to the problem of fluctuation. One of these has to do with bait.

According to Banoub, “The development and improvement of the cod fishery required a constant and abundant supply of bait” (66). He quotes a 1906 report on the fishery for the Governor of Newfoundland which describes bait fishes – squid, caplin and herring – as “the lanyard of the mainstay, without which it [the cod fishery] would be of no use.” The value proposition of saltfish production rested upon prior and dependable access to baitfish, the supply of which was prone to fluctuation. “Like cod,” Banoub writes, “the primary bait species were subject to variation over time and distinct spatial discontinuities” (67). Fluctuation made it difficult to coordinate the bait fishery and the cod fishery, a challenge that carried “serious pecuniary consequences, and controlling its supply emerged as one of the Fisheries Commission’s central preoccupations” (67).

As any self-respecting (Canadian) media studies scholar would know, the solution to problems of temporal and spatial coordination, or logistics, particularly when it comes to resource commodities and economies, is communication – the movement of a thing between one place, or one time, and another, such that a working relationship is established between them (Innis 1940). And communication is a matter of transmission and storage and the media that enable these operations.*

So, it comes as no surprise that the first attempt to manage fluctuation in the supply of bait involved a system for transmitting information about the changing location of bait fishes at any given time. In 1890, in partnership with the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, the Fisheries Commission set up a Bait Intelligence Service, through which information about the movement of baitfish was collected from 56 telegraph stations and communicated to fishing centres around Newfoundland (Banoub, 68-69). The service was short-lived (despite its public utility, it was not profitable for the telegraph company).

Telegraphic transmission of information across the space of the island provided a spatial fix to the problem of fluctuation, but it was soon superseded by an even more effective temporal fix grounded in storage. It is worth quoting Banoub at length here:

“The dissemination of accurate information regarding baitfish was considered a boon, but it paled in comparison to the possibilities offered by cold storage, or the preservation of bait by refrigeration…Stocking the bait depots when bait was plentiful, it was hoped, would ensure a constant supply throughout the season, finally overcoming the uncertainties of bait supply. Preservation by ice would freeze bait in time and space, allowing it to be stored and moved at will” (69).

The first experimental bait freezer in Newfoundland was put up at Burin in 1892. By 1904, eight additional refrigerated baitfish storage depots were established, including one at Fogo. That year, the government of Newfoundland passed a bill encouraging construction of a colony-wide cold-storage system, a process that proceeded in fits and starts until the mid-1930s when several additional bait depots were constructed (one at Joe Batt’s Arm), including a steamer ship converted to a floating cold storage unit that could distribute frozen bait to outports as needed. In 1937, the Bait Intelligence Service was re-established, broadcasting daily reports on the location and availability of baitfish.

Over this period, information about living baitfish transmitted via the medium of the telegraph and storage of captured baitfish via the medium of ice, combined to stabilize fluctuation in the bait fishery, a necessary precursor to industrialization of the extractive cod fishery. It turns out “the fish” did not come first. The bait did, and acquiring it in a manner suited to commodity production – its formal subsumption, we might say – required extensive mediation prior to the moment of codfish extraction. At least, that is, until the next phase of capitalist exploitation of “the cod” as a resource commodity, when factory trawlers arrived to harvest cod offshore in massive quantities by net, obviating the need for bait, but also eventually relying on ice, instead of salt, as a storage medium – a development that can be properly described as the real subsumption of the Newfoundland cod fishery to capital, the material and mediated transformation of the work of making fish into a form optimized for capital accumulation.**

Energy scholars will be familiar with this dynamic in other contexts. Malm’s famous account in Fossil Capital (Verso 2016) of the transition from waterpower to coal-fired steam power in industrializing England is similarly a story of capital responding to the problem of fluctuation with alternative media and formats. “Flow” energies, whose variability and boundedness to time and place enforced limits on capitalist accumulation and power, were replaced with “stock” energy that could be stored and transported for use wherever and whenever capital needed it. This entailed new techniques of mediation, new infrastructures and changing formats. As with the conversion of baitfish from a place- and time-bound flow to a stored and portable stock available anywhere, anytime, transition from the energy of flowing water to stocks of coal was a precursor to the real subsumption of productive labour to capital.

Fossil capital. Cod capital. Cultural capital. It is perhaps not surprising that a student of energy would sense this on the wharf at Seldom in those slabs of squid, frozen for bait, now once again necessary for the inshore line fishery that reopened in 2024, after offshore industrial trawlers did their work and exhausted the cod stock to a mere one percent of its historical levels, prompting a 1992 moratorium that led to the largest industrial closure in Canadian history. The cod are not coming back, at least not as an industrial-scale commodity capable of sustaining the economy of these islands. Still, those slabs of frozen squid got me thinking about bait, the “lanyard of the mainstay,” and the moments prior to extraction. Thinking about that spectacular inn and those enigmatic studios on the rocks at the edge of the sea in Joe Batt’s Arm on Fogo Island – fetish objects, stored in frozen images transmitted by lines connected to screens all over the world, where a resource lies waiting to be made. Like bait.

* on storage, see Daniel Banoub and Sarah J Martin, “Storing value: The infrastructural ecologies of commodity storage.” Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 2020, 38(6) 1101–1119.

** on salt as a medium, see Liam Cole Young, “Salt: Fragments from the History of a Medium.” Theory, Culture & Society 2020, 37(6) 135–158.

Text and images by Darin Barney, May 2025